Kitchens

- Category Name

- Kitchens

Get an approximate budget for your kitchen design by sharing your space details.

Speak to our design professionals

Share your info, we’ll book your slot.

Will you be living in your space during the renovation?

Previous Question

Previous Question

Previous Question

Previous Question

Please Select Date and Day

Appointment Date & time

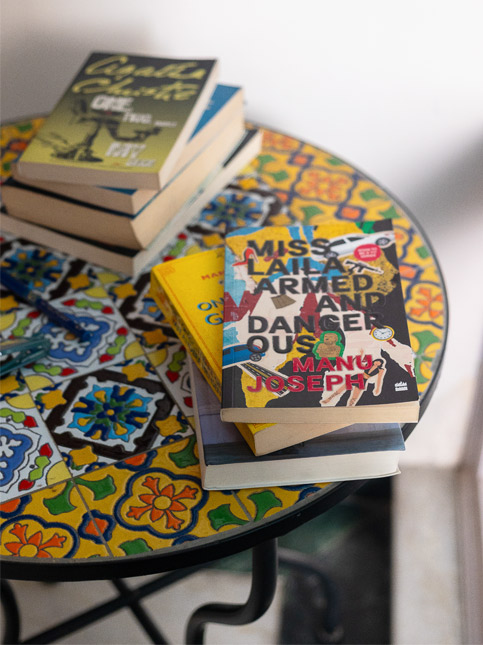

Desks, like reliquaries, become charged with the aura of those who leaned over them. For Manu Joseph the desk is mostly a trick, and he tell us why

The writer’s desk is one of culture’s most enduring myths. A square of wood, a scattering of paper, a lamp that burns into the night—it is imagined as the crucible where genius takes shape. Virginia Woolf made it a condition of freedom; William Faulkner, a daily battlefield. R.K. Narayan’s desk in Mysore is now a site of pilgrimage, a relic that devotees hope still hums with his sentences. Desks, like reliquaries, become charged with the aura of those who leaned over them.

But for Manu Joseph, the desk is mostly a trick. “Everything about writing and writers is a privilege,” he says, “and it fools a lot of poor people.” Where others might see sacred wood, Joseph sees scaffolding—class, inheritance, and networks, disguised as struggle. He does not worship the desk; he dismantles it.

Joseph’s own desk is modest, a wooden centerpiece in his living room, where clutter accumulates as easily as thought. But he insists the real function of a desk is symbolic: a stage on which readers imagine genius unfolding. “Writers from modest backgrounds are often shocked when they enter the field and find no doors open to them. Their lives might seem exotic enough for one book, but beyond that, even the readers themselves are too privileged to care. They want to read their own world.”

In Joseph’s telling, the desk is not a homeland, as Sumana Roy once called it in How I Became a Tree, but a trap. Roy’s words—“A desk is not a piece of furniture. It is a homeland”—complicate his pragmatism, suggesting that even within privilege there is longing, and even in pragmatism, vulnerability. Joseph strips the desk of mystique; Roy re-enchants it. Between them, the desk becomes both exile and belonging, illusion and anchor.

History, too, sides with enchantment. Thomas Carlyle’s desk was an altar of Protestant discipline. Gustave Flaubert’s was a temple of aesthetic obsession, every scrap meticulously arranged. In India, Narayan’s desk is preserved behind glass, proof that we still believe creativity can be tethered to a surface. Culture cannot resist turning desks into monuments. Even as Joseph shrugs them off, the myth persists: to look at a desk is to believe, however naively, that genius leaves behind a trace.

Joseph’s irreverence is his signature. His novels skewer myths with wit—Serious Men exposed the absurdities of caste and science; The Illicit Happiness of Other People rendered suicide and philosophy through family comedy; Miss Laila, Armed and Dangerous tangled with terror and paranoia. His most recent book, Why the Poor Don’t Kill Us, continues that project—part social commentary, part moral inquest—an examination of resentment, aspiration, and the fragile architectures that keep societies from burning. His columns for the New York Times and Mint drew both admiration and ire for their refusal to flatter. He does not protect illusions; he points at them, laughs, and watches them collapse.

Readers are not spared. “They might tolerate some kind of grime stuff for some time,” he says of books about poverty. “But what they all want to read is their own world.” He admires Sujatha Gidla’s Ants Among Elephants as a rare memoir that should define India, but he knows it remains an exception: most readers are too privileged to look for lives unlike their own.

Language, too, reveals Joseph’s sensitivity to illusion. Once, English was the unassailable key to upward mobility. “Ten years ago,” he recalls, “I wrote in the New York Times that there is no job in India, no legal high-paying job, that you can get without English. Now, that has changed.” English still carries prestige, but its power has weakened. “The saddest thing that the poor and the lower middle class do is not understand prestige,” he says. “The moment they can do it, it means it’s over. That is the nature of prestige.”

Prestige, in his telling, is always a vanishing trick—like chasing a mirage. For one generation, convent English might be salvation; for the next, it is merely baseline. The desk, too, is such a mirage: by the time a writer arrives at it, the horizon has already shifted.

Joseph carries this same suspicion into his views on technology. He approaches AI with dry amusement. “ChatGpt is basically like having a bullshit friend,” he says. “It is excellent for very talented people. And it will be very confusing for middling people who are at the level of ChatGpt.” AI, he insists, cannot conjure the fire. “Somebody sent me a Seinfeld script written by ChatGpt. I read it. The only thing it was not—was funny. And the only thing Seinfeld is, is funny.”

Still, he welcomes the machine as a tool. “It’s very good for formatting. I use it for formatting.” But what matters in art, he insists, is not form but experience. “What ChatGpt is not able to get even now is the humour part. That’s the key.” AI can sketch the outline of the crucible, but it cannot summon the flame.

And, so, his desk allows technology a corner, but never the center. What AI cannot imitate is the human spark: humour, rhythm, the strangeness of lived experience. At this desk, Joseph defines writing not as emotion but as the ability to see beyond it. “The most interesting and meaningful aspect of writing in my opinion is the ability to see through emotions. To me, a writer is someone who can see that extra layer in everything.”

That layer, he insists, is not moral. He distrusts the postures of solidarity that come so easily to writers. “Everybody has a quota of empathy, which they expend where it is easy. But when the stakes are high for you, you suddenly have a conservative position.” The desk, then, is too often a stage for moral theatre.

From there, Joseph steps outward. The world, he argues, is not collapsing because of villains, but because of democratisation. As more voices rise, the myths that once held society together lose their grip. “As more and more people are empowered… it leads to this kind of collapse and chaos where people can take a shot at it.”

And then, the line that lingers: “Practical men have won.” Trump. Modi. Putin. For Joseph, their triumph is not outrage but fact. “They are saying: this is how the world will be run.”

The words hang like smoke. Here, I feel my resistance stir. Because to call them practical is to mistake theatre for reality. Modi meditating in the Himalayas, Trump tweeting in all caps, Putin riding bare-chested on horseback—these are not acts of practicality but of stagecraft. They sit at their own desks surrounded by scripts, playing roles as carefully as any novelist. Power itself is a kind of literature.

And so, against Joseph’s certainty, I return to the desk. Not because it defeats the practical men, but because it unmasks them. The desk is a mirror, showing the emperor his costume.

Joseph rejects the idea of writers as shamans or moral guides. “Objectivity is a personality type—and that is the writer type,” he says. He sees the desk not as shrine but as dissecting table. Yet even in his refusal of illusion, he cannot escape it. To sit at a desk is always to perform, to enact the role of writer, even the role of dismantler.

And perhaps that is the enduring truth of the writer’s desk. It holds contradictions: homeland and trap, illusion and clarity, privilege and defiance. Joseph insists practical men rule; I reply they are storytellers too. He insists writing is privilege; I reply privilege itself is a fiction maintained by language.

The desk does not settle the argument. It only records it, line by line, quote by quote. A piece of furniture that becomes, in spite of itself, a witness.

All images by Kshitish Pandey (Ruuhchitra)

For expert design consultation, send us your details and we’ll schedule a call

Yes, I would like to receive important updates and notifications on WhatsApp.

By proceeding, you are authorizing Beautiful Homes and its suggested contractors to get in touch with you through calls, sms, or e-mail.

Our team will contact you for further details.

We were unable to receive your details. Please try submitting them again.